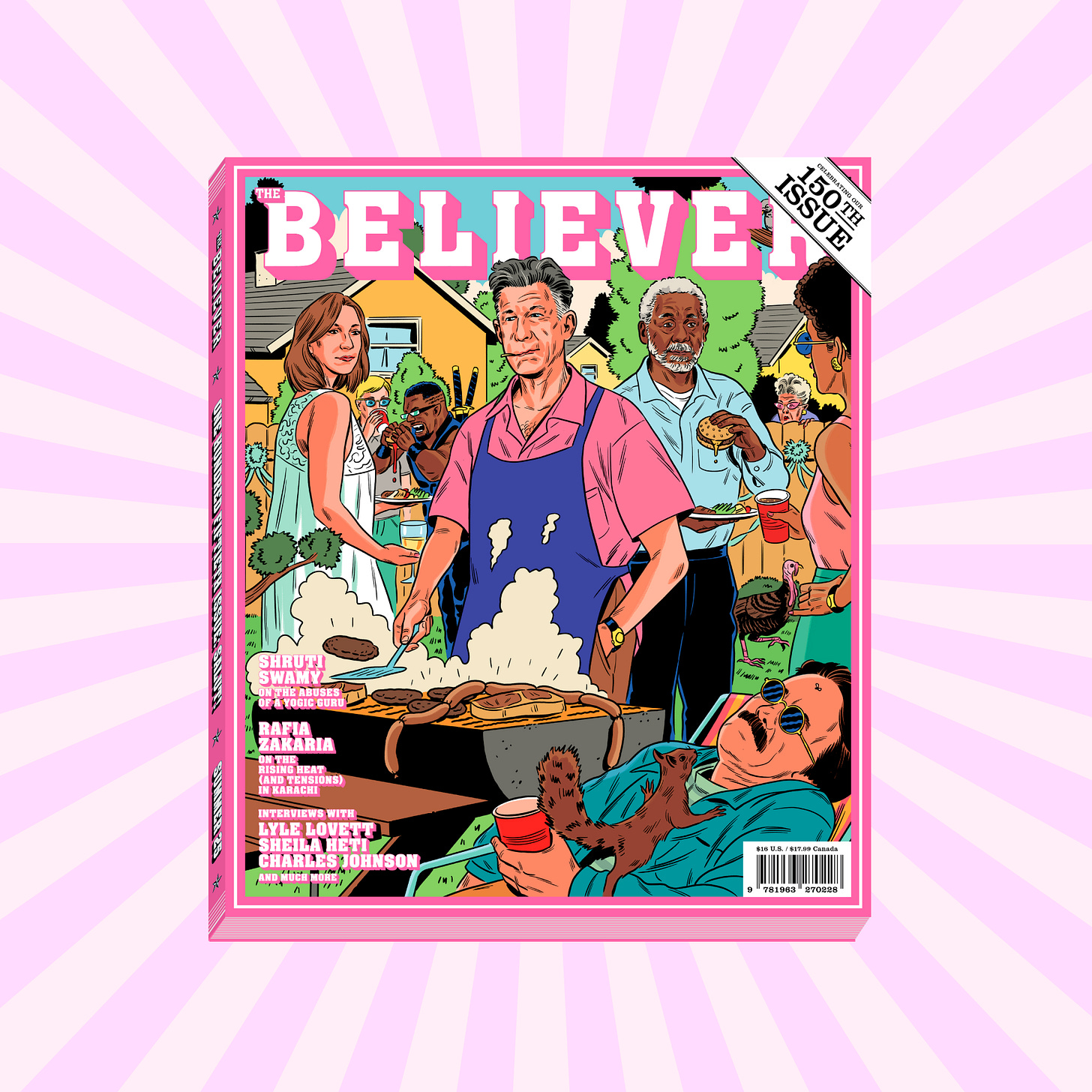

Inside our 150th Issue

Rafia Zakaria on the fraught quest for water and power in Karachi, Paul Collins on the largest newspaper ever printed, Lyle Lovett on what it means to be a cowboy, and much more

After twenty-plus years, we’ve made it to issue 150 of The Believer.

To celebrate this milestone we’re throwing a flash sale from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. PST, where you can pick up a yearlong print subscription for 40% off. That’s four issues for just $35—and 150% satisfaction guaranteed.

Subscribers will also receive some commemorative extras: a poster of Kristian Hammerstad’s signature interview portraits, a special letters section, and an extensive index of every issue we’ve ever published (or at least as best as we can remember things—it’s been a long time!).

And that’s just the start—read on for a look at some of Issue 150’s featured essays, interviews, and columns, previewed below.

We remain ever grateful to you, dear Believer readers. Thanks for sticking with us for 150 issues. Here’s to 150 more. Rejoice! Believe! Be strong and read hard!

—The Editors

Water Pressure

The difficulties of procuring water and power in Karachi, Pakistan, where surging temperatures have strained the city’s resources, and much more

by Rafia Zakaria

In the middle of the summer of 2024, when the temperature in Karachi was skirting 104 degrees Fahrenheit, a man was walking past my paternal aunt’s house. The sun was high in the sky at midafternoon, and he had just returned from offering his afternoon prayers at the nearby mosque. He did this every Friday, the holiest day of the week for Muslims, and the day on which the week’s main sermon is held. When he passed by my aunt’s home, he saw that water was overflowing out of her underground tank and onto the street. This annoyed him a great deal. Water envy is common in Karachi, a city that doesn’t have enough water for its twenty million or more inhabitants. Water comes through the municipal pipes for only an hour or two each day and sometimes not at all. Many homes that are not apartments have underground tanks in which water from the pipes can be stored. In most single-family homes, including my aunt’s, water must then be pumped to an overhead tank on the roof so it can flow out of the faucets….

One day not long after that sweltering Friday afternoon, so hot that even birds would not fly, this man—who is the sort of vigilante that retired men of a certain age can be—passed by my aunt’s house again. He was stunned to see that, yet again, water was flowing out of the underground tank and onto the street’s parched asphalt. If last time he had been annoyed at seeing this largesse of water, this time he was angered. In the past week, no water had flowed into his own tank at all. By Thursday the lack of water in his home had become so acute that he had had to purchase a private water tanker in order to shower and do household tasks like laundry and dishwashing. The tanker had not arrived until 9 p.m. the previous evening, an hour by which he would have liked to have been settled in front of the television. As a result, he was cross not only about having to spend money—something he truly disliked—but also about having his routine thrown into disarray.

All this exacerbated his indignation, added to which was the fact that he felt he “deserved” the water more. Why, after all, should a reclusive widow’s home be blessed with such a bounty of water when he was being denied his fair share? This time he decided he would not leave until he could deliver his own sermon on waste to the homeowner, loud enough for all the other neighbors to hear. For this to be possible, he needed someone to answer the door. Standing on the street, as the rivulets eddied around his sandals, he began calling out and ringing the doorbell. He would not, he resolved, leave until and unless someone responded to him.

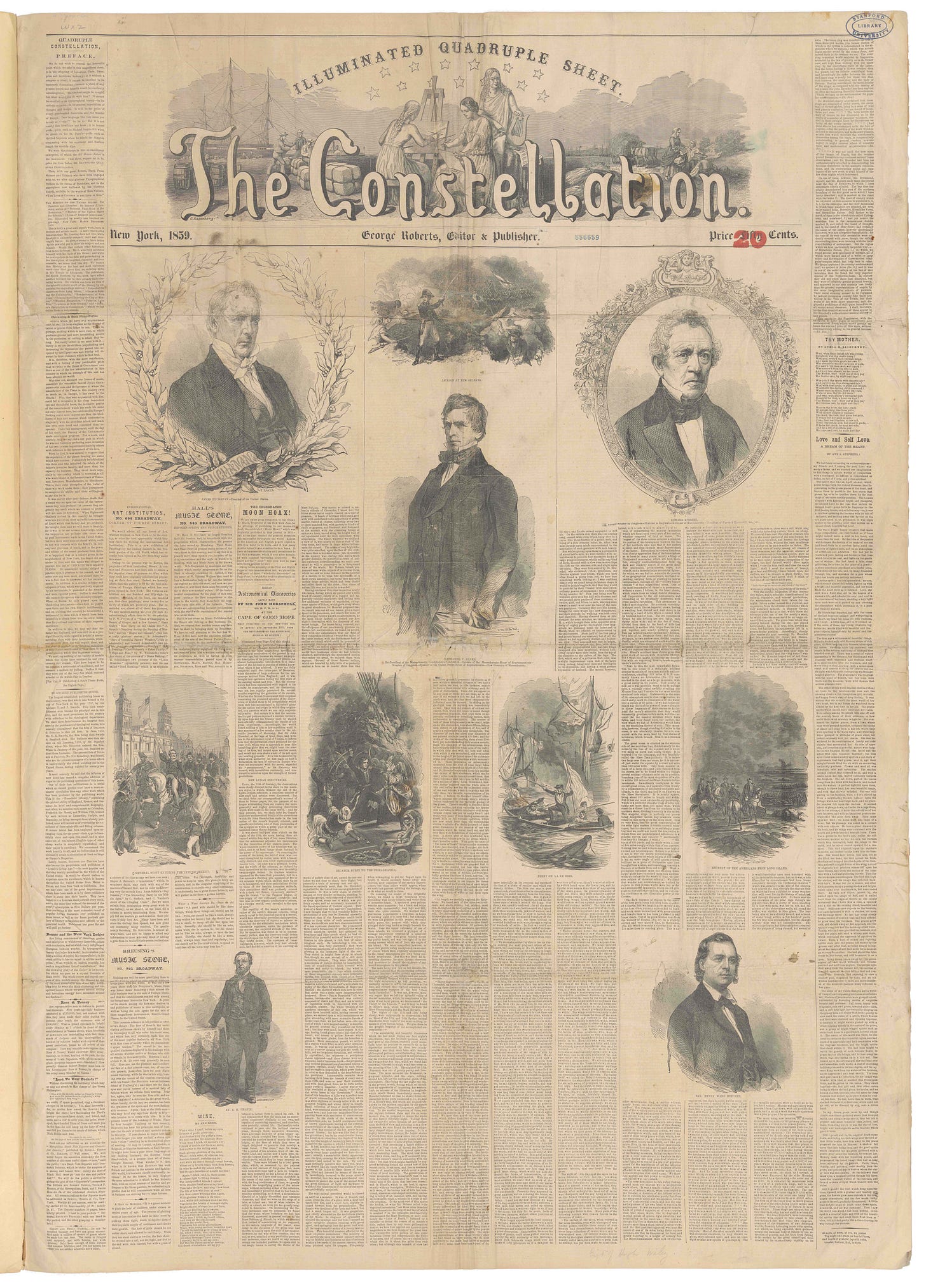

The Last Mastodon

The short and disastrous life of the world’s biggest newspaper

by Paul Collins

I hesitate a moment at Stanford University’s Special Collections desk. “I got in touch about seeing the Constellation? The newspaper from 1859?” I ask Tim Noakes, the library’s head of public services.

“Oh”—he motions toward the front of the room, where a newspaper sprawls over an entire reading table—“the big one?”

An act of typographical hubris that long held the title of “world’s largest newspaper,” the July 4, 1859, special issue of The Illuminated Quadruple Constellation survives today in only a handful of libraries. Published in Manhattan and distributed nationally, it was printed on seventy-by-one-hundred-inch sheets—bigger than a king-size bed—and then folded twice to produce eight pages, each fifty inches long and thirty-five inches wide. Its footprint can hold roughly six copies of The New York Times. When I lay my phone down next to a copy in Stanford University’s rare books room, the effect is of a tugboat bobbing in the water next to a battleship.

One page of The Illuminated Quadruple Constellation is the size of 117 iPhone SEs.

“It cannot be excelled in its mammoth dimensions,” brags the front page, “because a sheet of any greater length and breadth would be absolutely unmanageable.” This is not an idle boast. Upon attempting to read this behemoth, I find myself walking sheepishly back to Noakes at his desk.

“We need two people to turn the pages,” I tell him.

An Interview with Lyle Lovett

by Melissa Locker

I can’t remember ever not wanting to be a cowboy. So, years later, to be inducted into the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame was a big deal to me. Johnny Trotter, who was inducted around the same time—a great horseman from out in West Texas—said in his induction acceptance speech something that was just absolutely true. You don’t call yourself a cowboy. You’re not a cowboy until somebody else says you’re one. So being called a cowboy, being referred to as a cowboy by the Hall of Fame, by other people—it truly is a real compliment because it speaks not just to skills you might have in working on a farm or a ranch, but also to character and to a way of life, to values.

An Interview with Sheila Heti

by Cara Blue Adams

I don’t know if I know what plot is. I think you just have to get someone to the end of the book. There are many ways of doing that. It doesn’t have to be plot. It can be the switching of moods that a person becomes addicted to experiencing, or a train of thought they become curious about, or a tone they want to stay in. There are so many ways to keep somebody inside a book and to make them interested in what’s going on.

An Interview with Charles Johnson

by Jeffery Renard Allen

When you set out to do something, and you’re a literary writer, you have to recognize that this book could be your last will and testament in language. Every book of fiction I’ve done has transformed me in some way, from the research to the writing. You write trying to get it right, not for fame and fortune. The novel is a form of communication through the best technique and the best thought and feeling that I can bring to bear. Oxherding Tale took five years to write. Middle Passage took six years. Dreamer took seven. Each book is the best I can give in terms of whatever I’ve learned in the way of craft, human experience. That’s why art matters.

Resurrector: Weekend at Bernie’s

A rotating guest column in which writers reexamine critically unacclaimed works of art

by Nora Lange

Weekend at Bernie’s is about being wealthy in America: babes, boats, fraud. According to my mother, Weekend at Bernie’s qualifies as a movie, not a film. In 1989, when the movie hit theaters, it flopped. The critic Roger Ebert said the twist wasn’t funny enough to carry the story forward. He hated it. But what he didn’t see, may he RIP, was that the one-note, unapologetically crass materialism was worth the rental price of seeing it through to the end.

Pick up a digital subscription to start reading today. Annual print subscriptions to The Believer include four issues, one of which might be themed and may come with a special bonus item, such as a giant poster, free radio series, or annual calendar. View our subscription deals here.